M&A growth can generate significant value. It can also be extremely stressful for corporate leaders. Once they set their sights on a target company, they start feeling anxious about pulling the trigger. Anxiety is common and understandable because so much is at stake given the high rate of failure of M&A deals. Harvard Business Review places the odds of acquisition failure somewhere between 70% to 90%.

Time also plays an important factor in the decision. Deals usually require urgent action due to the competitive nature of the market. As a result, leaders find themselves in the position of having to decide under time pressure, with significant uncertainty, and unfavorable odds of success. In this article, we explore strategic due diligence because it is the first critical event in a series and affects all activities downstream. If you get this wrong, the rest won’t matter. If you get it right, it alleviates a great deal of pressure and paves the way for success.

AT THE OUTSET

Strategic due diligence is a forward-looking analysis that examines the drivers of earnings and cash flow to determine if the target is a sound investment. As in any examination, strategic due diligence can vary in scope and depth. When executives take a narrow focus on the deal, or they don’t dig deep enough into the strategic position of the target company, they leave themselves exposed to potential threats.

Inadequate strategic due diligence gives investors a false sense of security. By taking shortcuts and failing to address the drivers of value and the core issues, the analysis offers no early warning or real defense against potential problems, leaving the deal vulnerable to failure. Some of the vulnerabilities you can expect later include undue risk, blind spots, false expectations, or paying too much for the acquisition.

Small problems turn into big problems.

TXU Corp’s undue risk. Take the buyout of the energy company TXU Corp for example. Several private equity firms, including Goldman Sachs Capital Partners, TPG Capital, and KKR, bought the company in October 2007 for $45 billion. The investment thesis relied on the projected increase in demand for natural gas in the U.S. Six months into the deal, the market for natural gas began to slow down; gas prices continued falling year after year after that. Eventually, the risk proved too big for the company to absorb, forcing bankruptcy because it couldn’t pay back $40 billion in debt used in the buyout. As it turns out, the strategic rationale was not sound.

AT&T’s blind spot. Another example is AT&T’s acquisition of NCR. At the time, NCR was the leading company in barcode scanners, point-of-sale equipment, ATMs and check processing systems. AT&T wanted to launch a new technology division to target the communication industry. So in 1991, AT&T purchased NCR for $7.4 billion. By 1994, it had lost more than $1 billion, and for a simple reason: the subsidiary’s customer base of telecom companies were also AT&T’s direct competitors. Telecoms wouldn’t buy from an affiliate and boost their competitor’s revenue, a blind spot that executives overlooked.

e-Bay’s false expectations. A third example is eBay’s purchase of Skype in 2005. The deal was justified on the premise that Skype would provide a better platform for e-Bay customers to communicate. In reality, customers didn’t see the value of Skype technology in conducting auctions. By 2007, eBay wrote down the value of Skype to $900 million, and eventually went on to sell it to Microsoft in 2011 at a profit. The reason the deal failed was that false expectations about customer demand for Skype products went unchecked and never materialized.

GE’s overpayment. A case in point is GE’s acquisition of Baker Hughes in 2017. The deal was premised on synergies combining GE’s oil and gas business with Baker Hughes technical services to help customers acquire, transport and refine hydrocarbons more efficiently and safely, at a lower cost per barrel. GE finalized the deal in July 2017 paying Baker Hughes shareholders a one-time dividend of $7.5 billion, contending it amounted to $76/share*. By November 2017, Hughes Baker shares were trading at $31/share, and GE began looking to exit. As reported by Bloomberg, GE distributed a strategy presentation to analysts and investors citing that Baker’s reliance on volatile commodity cycles was cramping GE’s style**. GE’s CFO Jamie Miller told reporters that they were looking for “Exit optionality.” The four-month period from July to November was too short for any synergy to take effect, which is not what failed the deal. The acquisition was a mistake in the first place, whereby GE overpaid $7.5 billion.

Why do highly capable executives get pushed into these situations? Overconfidence, haste, false consensus, herd mentality, fear of questioning, selective inattention. These acquisition horror stories could have been prevented with proper strategic due diligence.

EFFECTIVE STRATEGIC DUE DILIGENCE

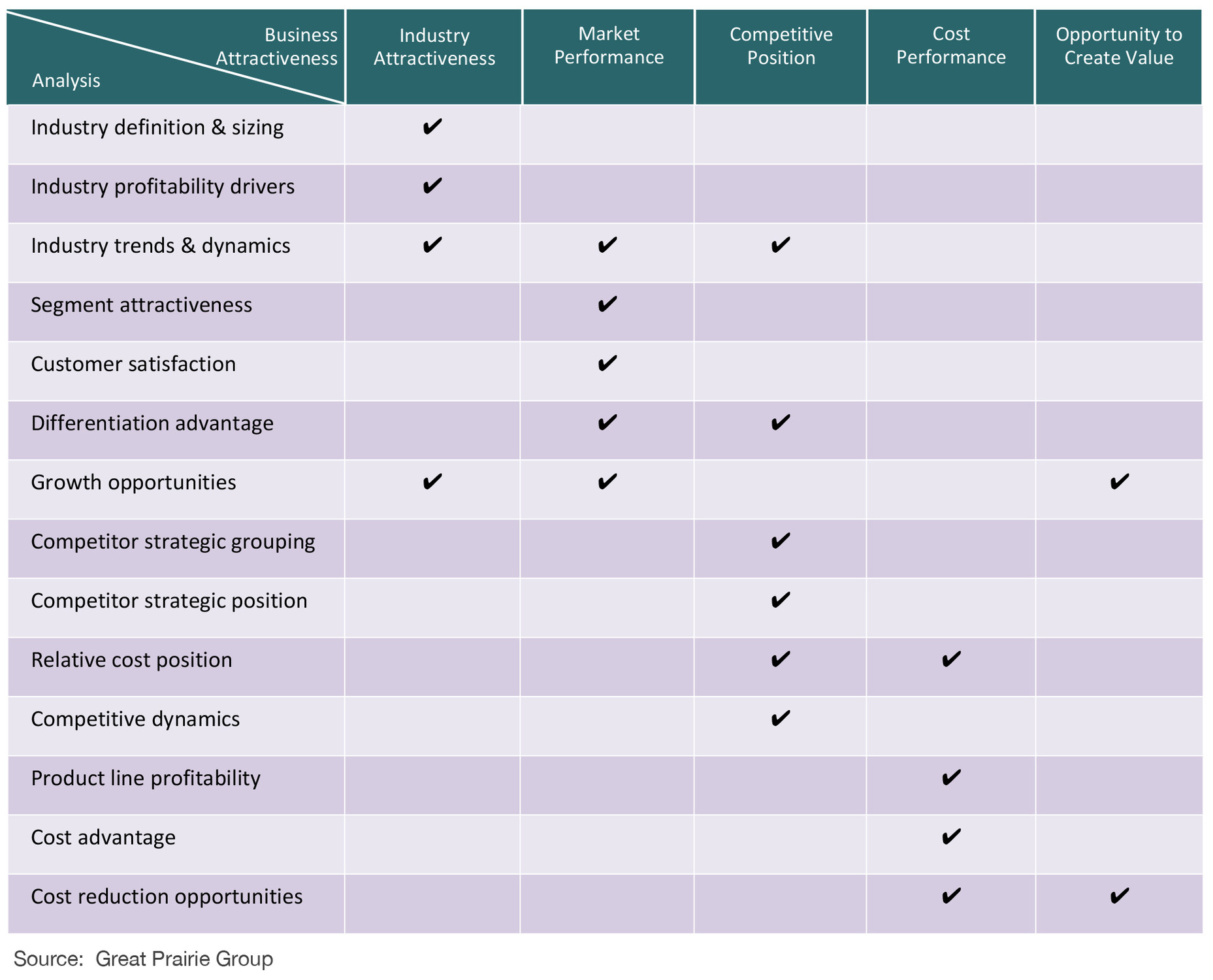

The objective of strategic due diligence is a forward-looking analysis to evaluate the stand-alone cash flow value of the target company. Strategic due diligence needs to take into account five elements of business attractiveness to be effective:

- Industry attractiveness

- Market performance

- Competitive position

- Cost performance

- Opportunity to create value

1. Industry Attractiveness. The industry environment within which the company operates has a direct impact on the level of competition and the profitability of the firm. Therefore, it is essential to understand the structure of the industry, how it operates, and where the value is created. Three analyses are particularly insightful:

- Industry Structure and Sizing: what are the geographical scope (global, national, local), the rationale for industry boundaries, its size, and growth?

- Industry Profitability Drivers: what are the underpinnings of competition and the drivers of profitability?

- Industry Trends and Dynamics: what are the forces and trends that shape competition?

2. Market Performance. A market comprises the set of customers that buy goods and services from competitors. Customers are grouped into market segments because they are not homogeneous, in that they buy products and services of varying quality, convenience, and price. Thus, the choice of segments served by the firm, how well, and the basis of differentiation from competitors, are fundamental elements of the company’s value creation that need examining.

- Segment Attractiveness: what are the size, growth, real profit margin, and competitive intensity of the market segments?

- Customer Satisfaction: what is the level of customer satisfaction with the offerings of the firm?

- Differentiation Advantage: what are the sources of differentiation that the company may have regarding advantage relative to competitors; e.g., market share, channel perception, brand loyalty, etc.?

3. Competitive Position. The profitability of the firm relates directly to (1) its ability to serve customers better than the competition, and (2) its ability to protect future profit streams against attack. The goal then is for the firm to build a strong competitive position to defend against direct competitors, as they represent the biggest threat. Three analyses are especially relevant in determining the company’s competitive position:

- Competitor Strategic Grouping: what are the major axes of competition? How are competitor groups deployed? Who are the direct competitors of the firm?

- Competitor Strategic Position: what is the strategic position of each direct competitor and its potential to retaliate?

- Competitive Dynamics: what is the strategy of each player, including strategic initiatives? How can the firm compete to win?

4. Cost Performance. A position of cost leadership provides two important benefits to the firm. The first comprises high net margins, which can be re-invested back into the business to build its advantage. The second is the ability to lead industry pricing and undercut weak competitors. Three cost analyses are essential in determining the cost performance of the business:

- Product Line Profitability: what are the full cost and net margin of each product line given the accurate allocation of overhead cost and COGS? Which product lines are losing money that should be cut?

- Relative Cost Position: how competitive is the cost structure of the firm? What is the potential for creating a position of cost advantage within the business?

- Cost Advantage: what are the sources of cost advantage the company may have relative to its direct competitors; e.g., scale, proprietary technology, experience curve, tax advantage, etc.?

5. Opportunity to Create Value. Ultimately, these analyses serve to identify the opportunities available to the firm to create value, of which there are two types:

- Growth Opportunities: the determination of viable opportunities for business growth based on understanding the sources of growth and the company’s operational capability to capture that growth.

- Cost Reduction Opportunities: the assessment of potential cost reductions and the time horizon to secure these savings.

Exhibit 1. Strategic Due Diligence Analysis

TOP PERFORMERS

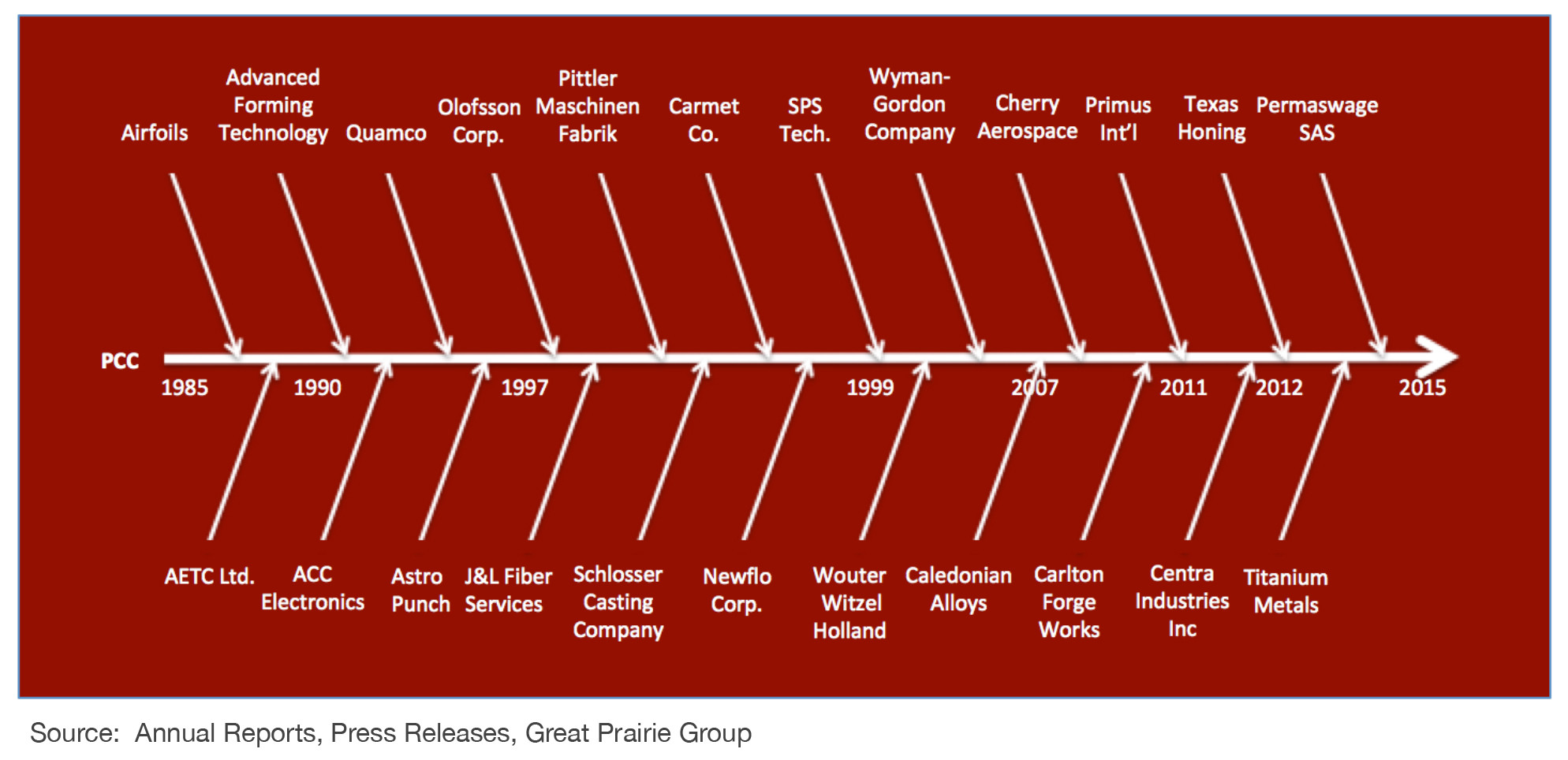

Companies that excel at acquisitions take a credible investment thesis and stress-test it with effective strategic due diligence. Precision CastParts (PCC) is a case in point.

PCC is an aerospace company that grew revenue from $41.5 million in 1985 to over $10 billion in 2015, at which point Berkshire Hathaway privatized it. During this period, the company made over 23 successful acquisitions; a track record is nothing short of stunning for any management team.

Exhibit 2. Precision CastParts History of Acquisitions

And PCC is not an isolated case. Other examples of excellent buyers include Valero Energy, Flowserv, Koch Industries, Roper Industries, PVH, and Chesapeake Energy, to name a few. What they have in common is that they stress-test their investment thesis with robust strategic due diligence.

OUTLOOK

If you are contemplating an acquisition, some constructive behaviors can prevent bigger problems down the road:

- never cut corners

- substantiate assertions

- prove your investment thesis

- get factual

- take a broad and deep look at the deal

- understand industry shifts and the underpinnings of industry profitability

- explain the core value drivers of the business and its competitive advantage

- evaluate the company’s strategic position

- stress-test projections

- quantify risk

- validate financial calculations

In today’s challenging M&A market, executives must be clear on their approach to an acquisition and in making strategic decisions that drive the future of their companies. If you want to excel at your next acquisition, your first step should be to stress test your investment thesis with effective strategic due diligence. Everything else depends on it.