Large corporations that operate in mature markets have a hard time growing at 5% to 7% per year. Many turn to annual re-organizations, on-going cost reductions, and divesting underperforming assets from their business portfolio. These actions improve efficiencies and limit the downside of poor portfolio performance; however, they do not add sufficient value.

Also, investors such as private-equity firms, hedge funds, and activist shareholders increasingly demand value creation from portfolio moves in companies they regard as too passive.

As a result, management can come under substantial pressure to create value by managing the business portfolio actively. This exercise is complex. However, a rigorous analytical approach exists and, ultimately, the payoff is enormous.

THE CHALLENGE

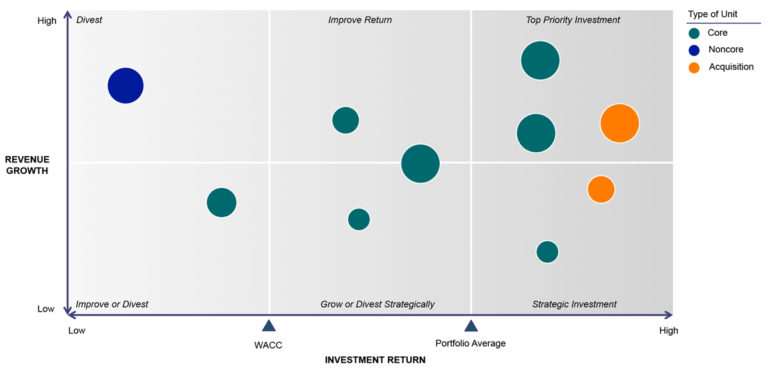

A preliminary disaggregation of the corporate portfolio into the individual units presents the current portfolio situation by combining the return of each unit and its historical revenue growth.

Returns above the average cost of capital (WACC) make for the creation of value. Conversely, returns below the cost of capital indicate destruction of value. The measures of return and revenue growth combined provide a frame of reference of the unit’s performance in growing value or growing loss (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1. Example of Portfolio Disaggregation by Business Unit

In this case, such a perspective displays an underperforming noncore unit that easily qualifies for divestment. It also reveals the opportunity for investment in two acquisitions. The logic of investing cash flows from a divestiture to more prominent opportunities is a critical portfolio move. However, it is not sufficient. Two reasons rise to the surface.

First, the crux of the opportunity to add value to the portfolio rests with all the units in between; this is where a company can make or break a business. Secondly, buying and selling units involves expensive acquisition premiums and integrations, which can zero out the value of M&A long term. Therefore, companies that actively manage their portfolio for value creation need to get beyond this traditional balancing logic to add value.

WHAT IT TAKES

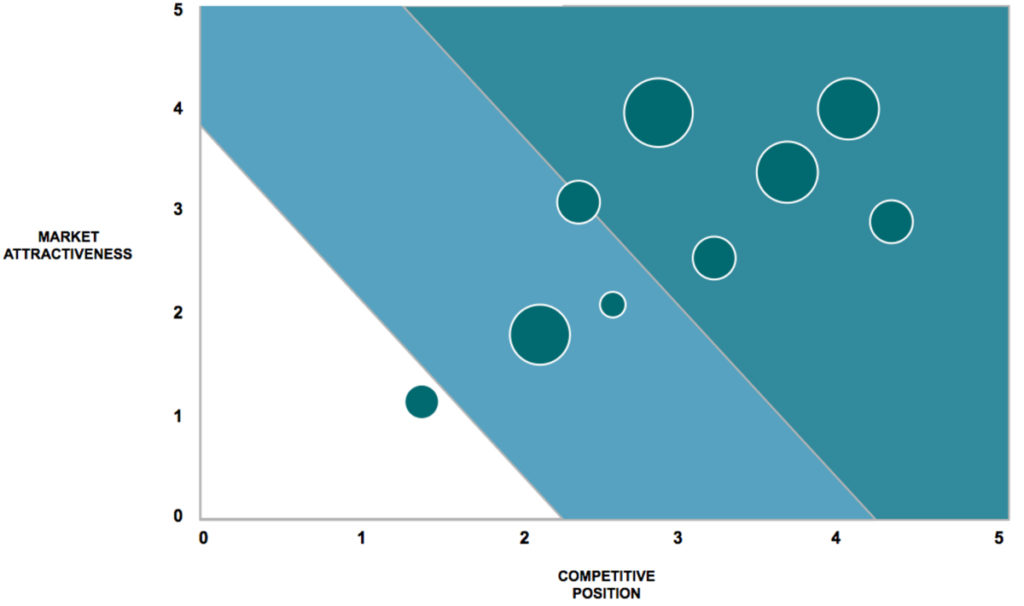

A business must be competitive in attractive markets to create value. Thus, actively managing a portfolio for value in practice means operating businesses that in aggregate (1) participate in attractive markets, and (2) are competitively positioned to win in those markets (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2. Competitive Position vs. Market Attractiveness

The primary order of portfolio management is to make sure that the business units are operating in attractive markets. If not, how well a unit performs doesn’t matter because there is little upside to be gained. This case usually calls for an exit.

If the business is operating in attractive markets but is not competitive, the second-order of portfolio management is to evaluate whether to improve the business or divest it. Generally, an underperforming business that is noncore merits divesting because it will be worth more to a different owner than the company. This case also calls for an exit.

In keeping the business, management needs to assess the top-down performance targets necessary for the business to sustain market share; these include scale, revenue growth, the optimal cost structure, and asset utilization. In parallel, the exercise requires deriving the initiatives to achieve productivity and growth targets.

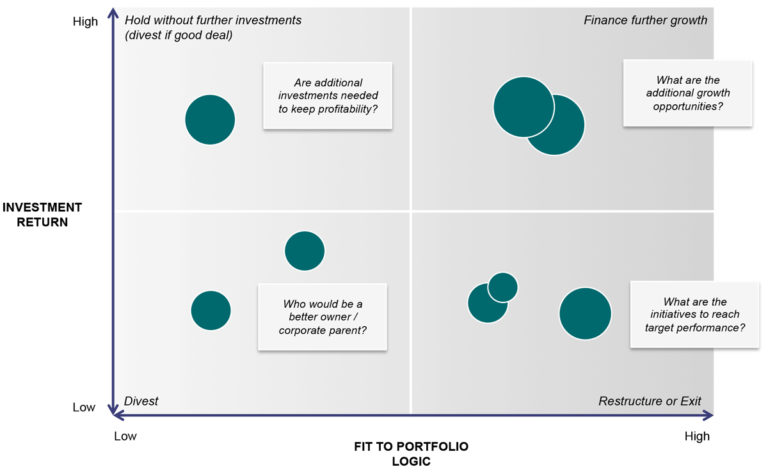

PORTFOLIO STRATEGY

The central logic of active portfolio management comes down to a clear portfolio strategy. Managers need to define the role of each business unit in the context of the corporate portfolio. Each unit has a unique position to play, and managers need to answer these questions: which businesses will comprise the growth engines? Which will provide growth in the immediate versus the long term? Which will supply the cash needed to finance overall growth? Require performance improvement? Which do we exit? Which do we fix to divest strategically?

Exhibit 3. Defining the Portfolio Strategy

Furthermore, management must be able to balance opportunity with capital to finance the initiatives. This step is essential because the amount of capital at the company’s disposal often doesn’t tally with the investment required by the opportunities, a condition that can sub-optimize the value of the portfolio.

RISK

Two types of risk are prevalent in managing the corporate portfolio. The first is the risk of inertia, i.e., doing nothing or acting late, which can detract significant value. A case in point is GE. In 2000, GE was a leading global company performing at the top of its game. Since then, it has missed the mark by operating in unattractive markets and taking too long to exit.

GE 2000 – 2018

GE’s activity in financial services began to deteriorate significantly in 2000. However, it wasn’t until after the 2008 – 2009 recession, when GE Capital almost collapsed the corporation, that management reduced its exposure. Similarly, management was late to divest GE Plastics and GE Appliances long overdue, only to focus on power and aviation – two sectors of low growth. During 2018, GE Power took huge losses given its failure to forecast a downturn in demand for its turbines that power natural gas and coal, amid booming demand for renewable energy. Furthermore, late in 2018, GE Power took a $23 billion impairment charge mainly related to assets associated with the acquisition of Alstom. As a result, GE’s annual average TSR has been -7% since 2000.

The second risk consists in making strategic errors. A prime example is Vivendi, a French global media conglomerate, that amassed many acquisitions by 2001 but lacked a coherent corporate strategy. There was never a business model, and the businesses had been assembled as a grab bag, which led the company to near bankruptcy.

VIVENDI 2001 – 2008

In April 2001, according to Jean-Marie Messier, then CEO “(We will be) the world’s preferred creator and provider of personal information, entertainment and services to consumers anywhere, at any time and across all distribution platforms and services.” In 2002, Vivendi took a corporate loss of €23.3 billion. The company began re-organizing in 2003 under the new CEO, Jean-Rene Fourtou, to avoid bankruptcy. It reduced its stake in Vivendi Environment, sold 80% of Vivendi Universal to GE to form NBC Universal, and reduced 50% of its participation in Canal Plus. It also divested several activities, including Vizzari, MP3.com, its Belgian and Dutch businesses, Monaco Telecom, Sportfive, its consumer magazines, and free newspapers, Newsworld International, and Babelsberg Studio. As a result, the company more than doubled its value from 2003 to 2008.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The importance of active corporate portfolio management is paramount and should not go underestimated. It adds significant value to the corporation, but equally as well, it can destroy value if neglected or poorly performed. Given its complexity, often managers adopt a gut-level approach to portfolio decisions, which can easily hit or miss the portfolio target performance.

Corporate leaders can set portfolio direction more confidently. A rigorous analytical approach exists in managing the corporate portfolio for value creation and is widely used by leading firms worldwide. The strategy reinforces a solid underlying logic, substituting gut-level decisions with sound rationale, ultimately creating significant value.