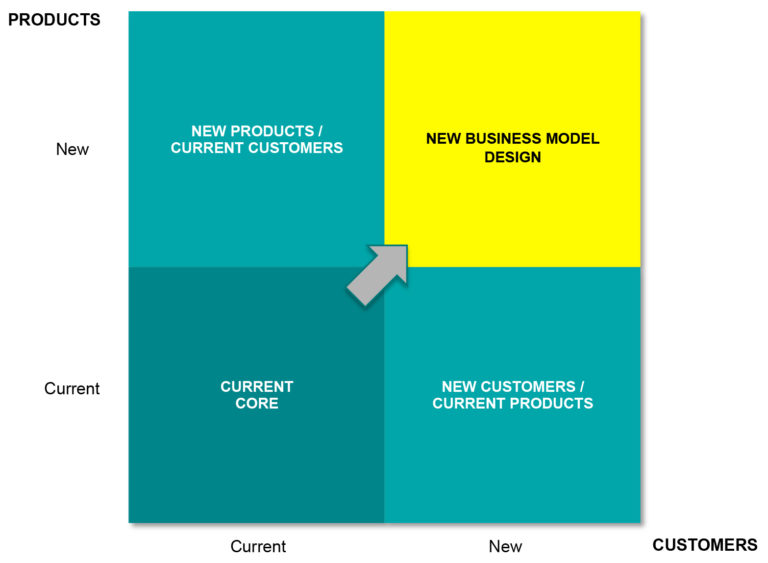

Entering a new market with new products that target new customers requires a new business model. It is a powerful strategic initiative that changes the rules of competition. It also represents a challenge with odds of success at roughly 30%, but ultimately – when done right – it rewards winners with huge returns.

Exhibit 1. Map of Adjacent Segments

WHAT IT TAKES

Managers need to know what they’re in for if they decide to pursue this path of business growth. The challenge in entering a new market through a successful business model innovation (BMI) consists of getting two elements right:

(1) the pursuit of attractive market opportunities, and

(2) ownership of the strategic control points in the industry to protect profit streams.

We look at cases of success and failure by companies that have entered new markets with new business model designs to illustrate the determinants of success.

SUCCESSFUL BUSINESS MODEL INNOVATION

Intel and SpaceX provide excellent examples of companies that entered new markets with new products through successful business model innovation.

CASE 1: Intel

In the early 2000s, Intel was the dominant manufacturer of microprocessors for the PC industry in the world. Two factors materialized to end this dominance: the slowing of PC demand growth beginning in 2000 and the rise of the low-cost PC. Also, competition intensified from AMD, which moved up from producing low-end microprocessors, as well as IBM and Motorola, close second and third in line.

These reasons drove management to innovate Intel’s business model design to become a supplier of integrated networking and communications for OEMs. The shift was a gradual transition to a platform for converging computing and communications to serve the telecom industry. The firm took the following actions to get there:

Market Opportunity

- Value proposition: moved from provisioning cost-effective processors to offering software and services based on an integrated platform combining multiple convergence-related technologies.

- Customer segments: shifted from OEMs, retail, online PC and mobile handset device manufacturers, to tablets, smartphones, automobiles, automated factory systems, and medical devices.2

Strategic Control Points

- Unique technology: The Intel® Internet Exchange Architecture (Intel® IXA) provided a flexible platform for the networking and communications industry to build faster, more intelligent networks using reprogrammable silicon.

- Participation in open standards: Intel participated in open architecture standards to promote industry-wide convergence.

- Large focused R&D: R&D efforts centered on accelerating the convergence of computing and communications, primarily through silicon integration, enabling the firm to deliver leading-edge technologies. R&D expenditures in 2005 amounted to $5.1 billion ($4.8 billion in fiscal 2004 and $4.4 billion in fiscal 2003).

- Patent ownership: The company applied for and received, in the aggregate, tens of thousands of overlapping patents annually in the U.S. and other countries.

- Manufacturing control: As of 2006, 68% of its wafer manufacturing, including microprocessors, chipset, NOR flash memory, and communications silicon fabrication, was conducted at its U.S. facilities. Outside the U.S., 32% of its manufacturing was performed at its facilities in Ireland and Israel.3

As a result of the new BMD strategy, Intel was able to increase its revenue 58% from 2006 to 2014, and raise its ROE to 21% by 2014.

CASE 2: SpaceX

The satellite launch industry had been consolidated and deadlocked for years. A few large players controlled a flat-growth global market. In 2002, Space Exploration Technologies Corp., known as SpaceX, entered the market with a revolutionary business model design that has since shaken up the industry. Over several years, management has taken a series of actions to place the company in a winning position.

Market opportunity

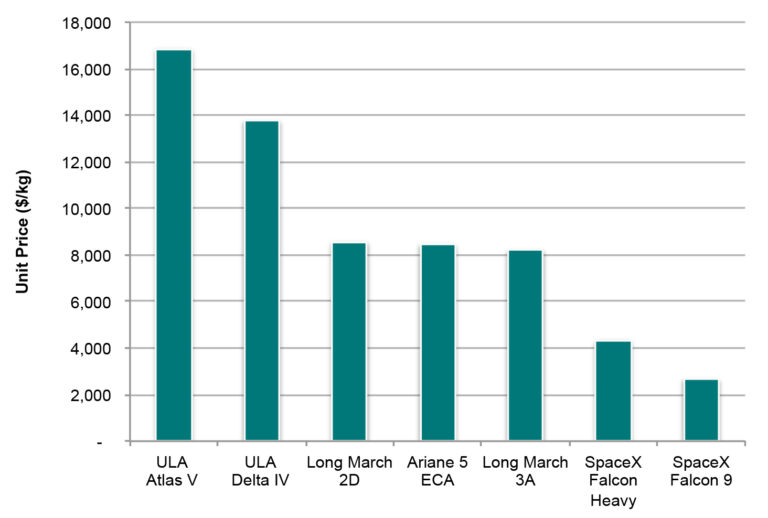

- Value proposition: Placement in orbit of two categories of satellites: low earth orbit (LEO) and geostationary (GTO), at prices well under 50% from its competitors.

- Customer segments: SpaceX has targeted the U.S. government and U.S. commercial market, measuring about $2.2 billion in 2016.

Strategic control points

- Owns breakthrough technology: the company has developed a unique technology for reusable stages 1 and 2 of the rocket booster

- Controls the value chain: production of the launch vehicles is extensively vertically integrated

- Enjoys cost leadership: the cost structure is 90% less than the United Launch Alliance (ULA).

- Price leadership: Thanks to its favorable cost structure, SpaceX can price launches well under 50% versus its competitors.

- Owns the customer relationship: The company has extensive contracts with NASA and the U.S. Air Force, the largest customers in the world, including China, Russia, and the European Union.

Exhibit 1. Comparative Unit Price for LEO Launch (2016)

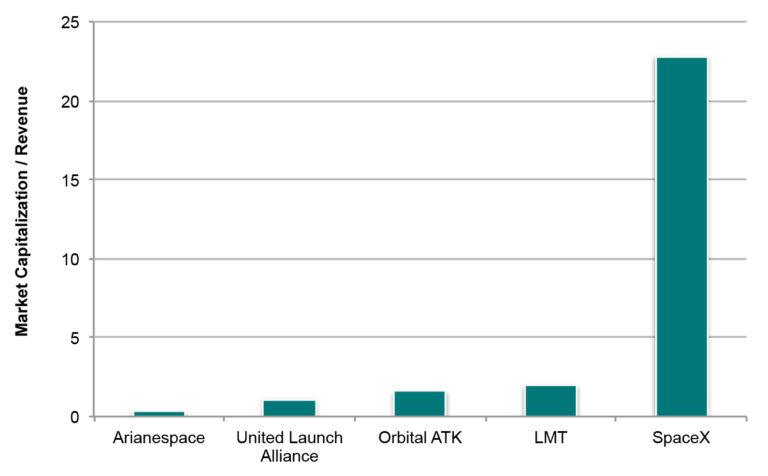

These actions have resulted in a market capitalization of $25 billion in 2017. A ratio of market capitalization-to-revenue of 22.5 makes SpaceX the industry leader.

Exhibit 2. Comparative Values of Market Capitalization-to-Revenue (2017)

FAILED BUSINESS MODEL INNOVATION

We look at two examples of failed business model innovation to learn what went wrong: Nokia and Swissair.

CASE 3: Nokia

Nokia entered the mobile phone market with incredible success. During its growth ascent, the company established itself as the largest vendor of mobile phones and smartphones in the world.

Market Opportunity

- Value proposition: The best mobile phones and smartphones in the world and second to none, including Motorola, Ericsson, Huawei, RIM, and HTC. Also, the company’s proprietary Symbian operating system was the standard platform for European carriers.

- Customer segments: Mobile phone subscribers in the U.S., Europe, Asian markets.

New entrants came into the market in 2007, including Apple, Google, Samsung, LG, among others.

Strategic Control Points

- Ownership of the industry standard operating systems – Google Android and Apple IOS were superior to Nokia’s Symbian, which was buggy, chunky, counter-intuitive for the customer and fell out of use

- Privileged information about customer preference – Apple began to deliver products that satisfied unmet customer needs, including multi-touch touch screens, apps, expanded memory, synchronization with other devices, and more

- Effective R&D programs – Nokia was unable to translate R&D spending into winning products, while competitors did

- Fast product development lead time – the name of the game in mobile telephony is constant innovation, whereas Nokia’s products were late to market and faulty

- Creating and maintaining a one-year lead over the next competitor – Apple banks on the first two years of new product release where pricing power is maximum, and the highest profits are made.

Unfortunately, Nokia was not able to hold on to its early success for long. The company missed securing the relevant strategic control points in the mobile telephony industry, a strategic error which proved catastrophic and eventually caused near bankruptcy for the firm. Finally, Nokia got out of the business by selling the unit to Microsoft in September 2013, who scrapped the activity a few years later.

Exhibit 1. Nokia’s Historical Market Performance

CASE 4: Swissair

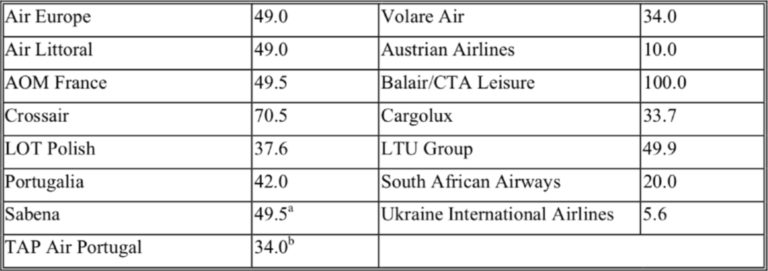

SAirGroup, more commonly referred to as Swissair, had long been aware of the limited growth potential of its home market with the country’s population of only 7 million. Due to high labor costs and the country’s strong currency, it was also one of the most expensive business locations in the world. As a result, the company had expanded into ancillary and non-aviation activities, including maintenance and repair, ground handling, IT, aircraft leasing, catering, duty-free, hotels, aerial photography, and agriculture. In 1997, the airline also created a Swissair-led and equity-based alliance: the Qualiflyer Group, populated with smaller non-aligned European flag carriers as its members.

Exhibit 1. Swissair’s Equity Stakes in Other Airlines (%, 2000)

Market Opportunity

- Value proposition: The alliance sought to funnel flights through Zurich and Brussels and increase passenger traffic among alliance partner airlines. The hub-and-spoke-system obligated almost all members to contract out their aviation-related services (ground-handling, maintenance, IT) to a SAirGroup company and lease their aircraft from FlightLease; another subsidiary specialized in sale-and-lease-back arrangements.

- Customer segments: It targeted niche segments, including smaller European countries and markets with enormous growth potential such as Belgium, Austria, Finland, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, and Ireland only.

Strategic Control Points

- Financial strength: Swissair committed substantial equity investments to buy stakes in the financially-struggling partner airlines to prevent its partners from defecting by establishing asymmetrical relationships in Swissair’s favor.

- Brand name: Swissair’s management diluted the company’s valuable brand by selecting second- and third-rate carriers as alliance partners, effectively only carriers that had been shunned by the other alliances.

- Pricing power: A tarnished brand increasingly undermined the carrier’s ability to extract premium fares from its passengers.

- Competitive cost structure: Given its intricate web of 260 subsidiaries, personnel costs reached 39% of the company’s total operating expenses, one of the highest percentages in the industry.

- Economies of scale: Given Swissair’s dispersed activities across many fronts and lack of scale, its ever-rising break-even load factor eventually reached 75%.

The alliance had taken the form of a new business with new cost and asset structures, new customers, and with Swissair controlling the center of the hub-and-spoke arrangement. During the time of the alliance, the company incurred financial losses year after year and eventually became insolvent. Swissair collapsed, grounded its operations in October 2001, and declared bankruptcy shortly after that.

THE PAYOFF

Intel generated substantial gains. SpaceX has outperformed all the players in the satellite launching industry. Other notable examples of successful market entry through BMI include Steel Dynamics in manufacturing steel rails, GE’s Power-By-The-Hour engine maintenance service, Southwest Airlines as a pioneer in low-cost passenger flights, Uber in ride-sharing, to name a few. In each case, the payoff was huge.

Conversely, Nokia got out of the business, and Swissair went bankrupt. Other examples of failed market entry through business model innovation include Blackberry, Lego’s “Design by ME,” Palm, Yahoo’s hosted services for SMEs, and SonyEricsson, to name a few. In each case, the failure was devastating.

CONCLUSIONS

Entering a market that requires business model innovation is risky. On the one hand, the payoff for success is significant, on the other, the consequences of failure can be devastating, and there seems to be little gray space in between.

Overall, companies appear to have a good sense of the market opportunities to pursue. Less apparent is their ability to secure the relevant strategic control points (SCPs), a setback which exposes the firm to the possibility of failure. Intel and SpaceX were successful by acquiring unique technology, essential patents, open standards, highly focused R&D, and manufacturing control.

Conversely, Nokia failed to secure control of the industry standard operating system, privileged customer information, effective R&D, and competitive product development lead time. Swissair lacked financial strength, tarnished its brand name, lost its pricing power, and missed a competitive cost structure and economies of scale.

The overriding concern about SCPs is one of relevance. Let’s look at the industries that we covered:

- Technology industries require owning essential patents, unique technology, de facto standards, and or effective R&D.

- Satellite launching demands advanced technology, a low-cost structure, competitive pricing, and strong customer relationships to be competitive.

- Electronic products need constant renewal to stay competitive which calls for fast development lead time and maintaining a one-year lead over the next competitor.

- Airlines need low-cost operations and an extensive route network to be competitive.

SCPs vary by industry. Companies need to figure out which are the essential control points in their industry and secure them. Doing so sets the foundation for a sustainable business model from which to pursue market opportunities. Without it, any market success is bound to be short-lived.

Citations

- “Beyond the Core: Expand Your Market without Abandoning Your Roots” by Chris Zook, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA

- “Strategies for business model innovation: How firms reel in migrating value” by Fredrik Hacklin, Joakim Bjorkdahl, Martin W. Wallin

- Intel annual reports.