Companies sell many products to capture a sizable portion of the market. In so doing, they can reach the limit of too many products and give rise to unintentional business complexity – in the supply chain, sales and marketing, product development, and administrative processes. The direct consequence includes increased costs, wasted resources, and significantly lower margins.

WHEN YOUR PRODUCT LINES WEIGH YOU DOWN

Many situations contribute to product proliferation and excessive costs. We explore four of the most common and significant ones:

- End-of-life-cycle product lines

- Product lines with significant overhead cost

- Small-volume low-growth product lines

- First-to-market product lines

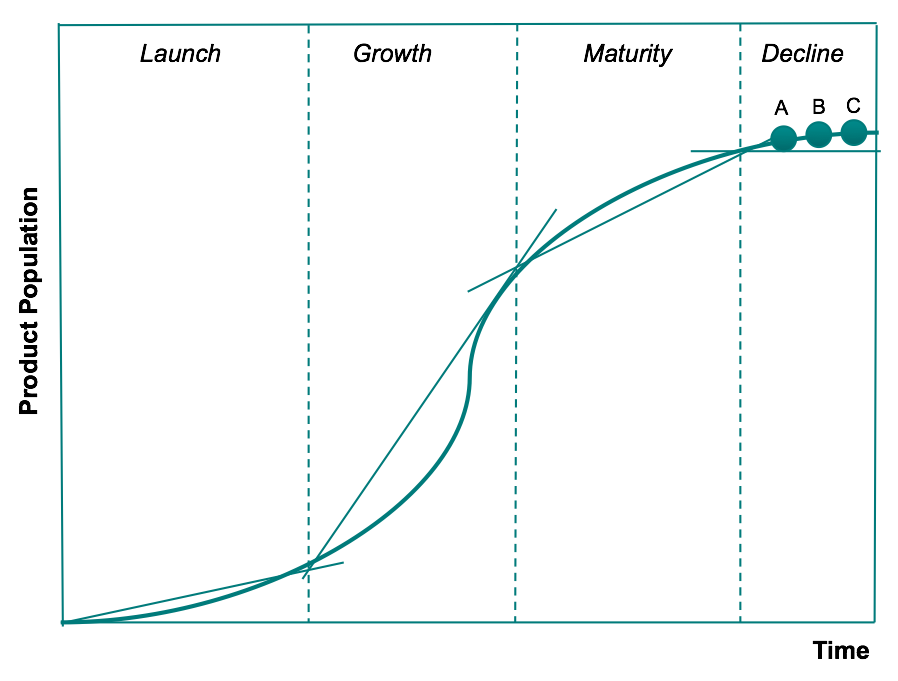

1. End-of-life-cycle product lines

Product lines in the last stage of a product’s lifecycle, end of life cycle (EOLC), generally serve few customers and carry considerable costs. The reasons are as follows: (1) parts are difficult to find because they are no longer being supplied, (2) EOLC products may not be compatible and need constant upgrades, and (3) they usually require a high level of technical support. The resulting overhead cost is disproportionately high because it cannot be amortized over large product volume. As a result, EOLC products are not necessarily profitable and may need to be retired, a decision that needs to be made in the context of a broader business strategy.

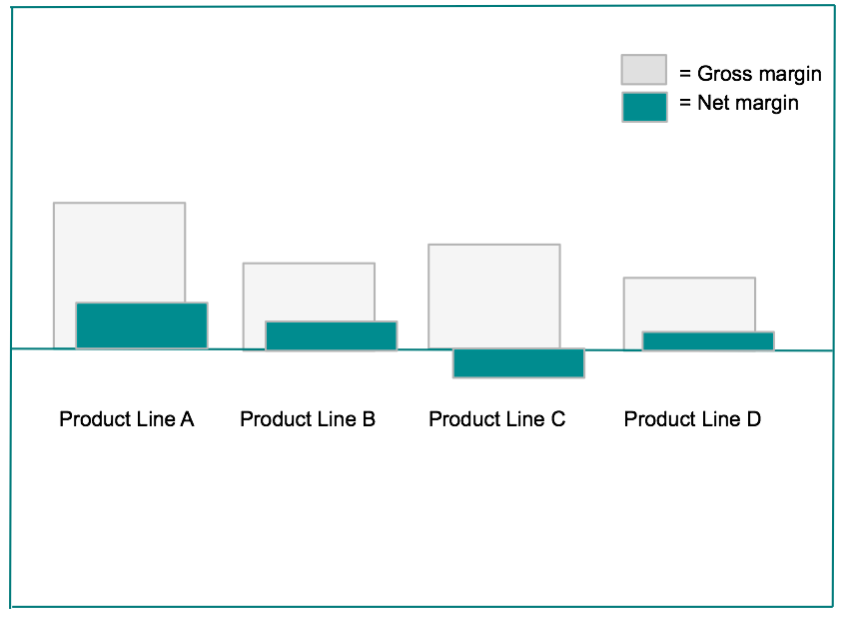

2. Product lines with significant overhead cost

Companies with asset-intensive operations incur significant overhead costs, including PPE depreciation, inventory carrying costs, and indirect labor to name a few. Traditional cost accounting arbitrarily adds a percentage of overhead expense to direct cost to allow for an estimate of total costs. As the rate of overhead cost rises, this allocation becomes increasingly inaccurate because costs are not caused equally by all the products. Unless overhead costs are allocated appropriately, product lines with actual negative net margins are not always visible to management.

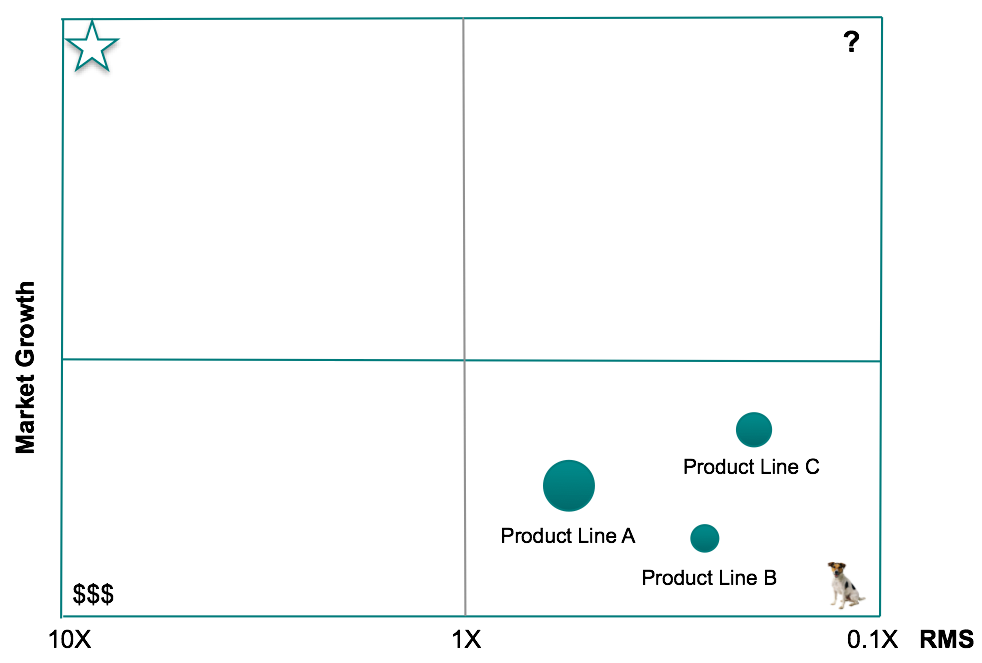

3. Small-market-share and low-growth product lines

Product lines with small market share and low growth, i.e., “dog” product lines, carry a significant cost. Given low share, these product lines don’t benefit from competitive economies of scale, they incur increasing inventory-to-sales ratios, and take increasing marketing costs as a percentage of sales. These product lines absorb disproportionately high overhead cost that cannot be spread across large product volume. As a result, these product lines are not always profitable.

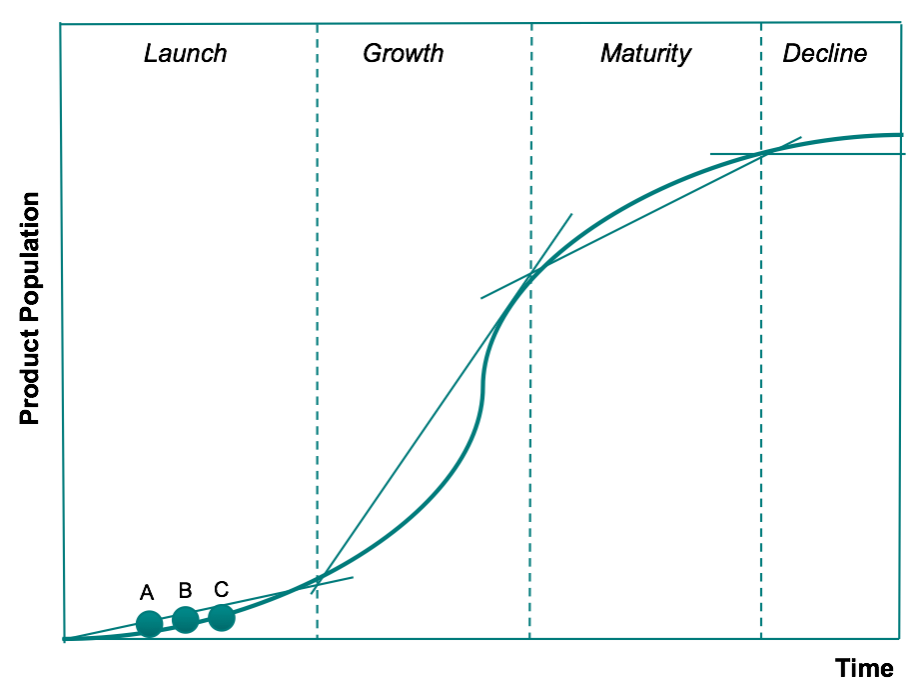

4. First-to-market product lines

The objective of being first to market with a new product or to quickly match a competitor’s new offering can blind-sight management from the potential downside of the added cost of complexity. Part of the reason is that the accounting systems are not always set up to capture all the costs of new products. Some of these costs comprise additional personnel time, including senior management, “extra” engineers and technicians, employees for marketing, preparation for manufacturing, prototypes and pilot runs. There are also out-of-pocket expenses that can add up to significant amounts, including expendable materials, travel, technical consultation, tooling, samples and pilot runs, rework, and product certification. Other financial implications include time to market and frequent delays. Few companies consider the full costs of added complexity.

Each of these product situations leads to business complexity and substantial costs that ultimately weigh down the company.

FIXING THE PROBLEM

The prescription for fixing value-destroying complexity is to respond strategically. We find that successful companies follow two principles to help recover from the downside of product proliferation:

- Rationalize unproductive product lines. Management needs to be able to account for the full cost associated with product lines. It needs to determine the actual profitability of the company’s product lines by incorporating costs not easily assigned to products (e.g., warehouse expenses, administrative expenses) and costs not considered product related (e.g., interest associated with financing inventory and accounts receivables). With this information, product-line decisions can be made in the context of a broader business strategy.

- Manage for value, not product variety. There are many ways to manage products for value:

- Cross-selling and bundling are obvious options

- Companies can also enrich products with information and services that help solve customers’ problems

- Finally, adopting the approach of providing integrated customer service has the potential to limit complexity.